Donna Adelson guilty: Phil Markel confronts her after verdict in Dan Markel murder case

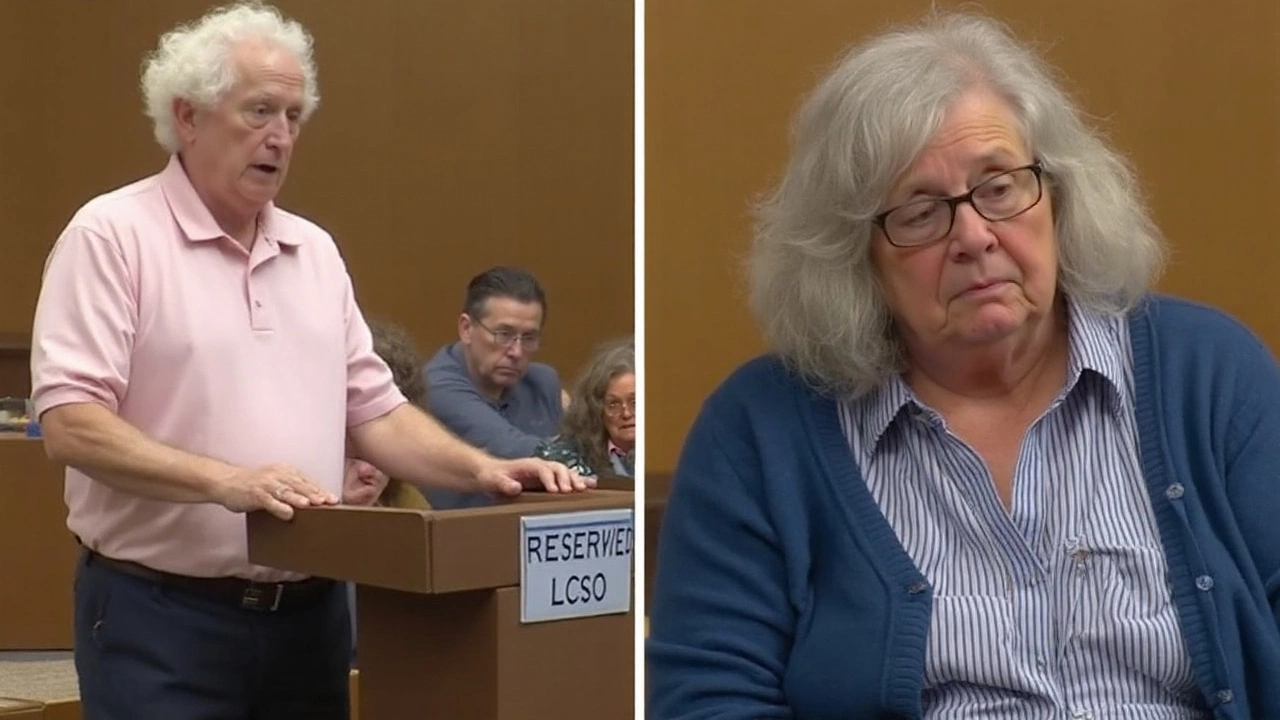

The question landed like a hammer in a silent courtroom: “Was it worth it?” Moments after a jury found Donna Adelson guilty on all counts in the murder-for-hire of Florida State University law professor Dan Markel, his father, Phil Markel, faced the woman prosecutors say orchestrated the plot and asked what had hung over this case for more than a decade. He also invoked an old blessing — wishing someone a long life — and twisted it into a rebuke: May she live to 120, alone in her cell.

It was the rawest moment of a long-awaited verdict. Jurors returned guilty findings on first-degree murder, conspiracy to commit first-degree murder, and solicitation to commit first-degree murder after a brisk deliberation. The date — September 4, 2025 — came more than 11 years after Markel was shot in the garage of his Betton Hills home in Tallahassee. Adelson, 75, now faces a mandatory life sentence for the murder conviction. A pre-sentence investigation will be prepared for the conspiracy and solicitation counts. The next court date, set as a case-management check-in, is October 14, 2025.

As the clerk read the verdicts, Adelson broke down. Across the room, Phil and Ruth Markel — who have carried their son’s story across courtrooms, hearings, and legislative halls — listened quietly. Their words afterward were brief, direct, and pointed at the woman they believe helped end their son’s life and fracture two families.

A verdict 11 years in the making

To understand how this moment arrived, you have to rewind to a case built step by deliberate step — the approach one prosecutor described as “patience and a plan.” Investigators and trial teams moved in stages, securing cooperation, stacking corroboration, and letting earlier trials establish pieces of a larger picture.

- July 2014: Dan Markel, a 41-year-old law professor at Florida State University, is shot in his garage after returning from the gym. He dies the next day.

- 2016–2019: Two Miami men, identified in court as the triggermen, are arrested. One pleads and testifies; another is convicted of first-degree murder. Phone records, cash movements, and travel traces are laid out in court.

- 2022: A woman accused of being the go-between is convicted at retrial, adding another layer of corroboration to the murder-for-hire narrative.

- 2023: A senior member of the Adelson family is convicted, tightening the evidentiary chain connecting money, motive, and contacts.

- 2025: Donna Adelson is found guilty on all counts, the jury embracing the prosecution’s theory that she was part of the planning and push behind the hit.

Across those cases, jurors heard variations of the same core story: a bubbling family conflict tied to a messy divorce and a blocked move with Markel’s children. Prosecutors said the motive was simple and ugly — to solve a family problem by erasing the person in the way. The state built its proof with a familiar mix: cell-site and call records, bank transactions, witness testimony from cooperating insiders, and recorded conversations introduced in related trials. Each piece did not have to carry the whole story. Together, they did.

The defense challenged the links, arguing that speculation had hardened into a narrative and that circumstantial threads were being stretched past their limits. But in the end, the jury accepted the state’s version, finding that the planning and solicitation flowed back to Adelson and that the murder was not a random act but a contracted hit.

Victim impact statements are not evidence, and in Florida, judges remind jurors of that before deliberations. After a verdict, though, those statements can shape the record — and on counts that are not mandatory, they can influence a judge’s thinking. Here, the life term attached to the first-degree murder conviction is essentially set. The pre-sentence report ordered for the conspiracy and solicitation counts will cover Adelson’s history, health, and other factors, then land on the judge’s desk ahead of a final sentencing hearing.

Don’t expect that to be the last court filing. A defendant in a first-degree murder case almost always appeals. Legal analysts tracking this saga anticipate a familiar list of issues: challenges to the admissibility of recordings and statements, disputes over expert testimony on phone and financial records, and arguments about how much of the earlier trials’ evidence should have reached this jury. Appeals are slow. Even a fast track takes many months.

What comes next — sentencing, appeals, and the case’s wider orbit

For now, the calendar is straightforward. The court has set an October 14 case-management date while the pre-sentence investigation is prepared. On the murder count, the judge will impose life in prison. On conspiracy and solicitation, the court will weigh the report, any mitigation from the defense, and the prosecution’s recommendation. Given the verdict, few expect leniency.

Could there be more arrests? Prosecutors have been careful, but their “patience and a plan” framing suggests they see this as a multi-branch conspiracy, not a one-off killing. The verdict inevitably raises fresh questions about the legal exposure of other figures who have hovered around this case for years, including Wendi Adelson. To be clear: prosecutors have not announced new charges, and speculation is not proof. But grand jury work is often quiet, and cooperation can take time to ripen. The state’s steady sequencing over the past decade has taught one lesson — do not assume the last chapter has been written.

The Markel family’s visibility has been unusual for a homicide case, but their advocacy has been focused and specific. They pushed for crime-victim reforms, stood behind prosecutors through multiple trials, and supported a Florida law nicknamed the “Markel Act,” which gives grandparents a path to seek visitation in rare circumstances when a parent is suspected or convicted in the death of the other parent. It was a response to a very particular pain: the fear that the murdered parent’s family would be erased from a child’s life.

Inside Tallahassee’s legal community, the verdict hits close. Dan Markel was a colleague, a mentor, and a voice in criminal law debates. The brutality of the ambush, coupled with the long arc of the prosecution, changed how many in the city talk about contract killings — not as Hollywood spectacle, but as something that can be plotted in text messages, bank withdrawals, and highway miles.

That’s why Phil Markel’s question cut the way it did. “Was it worth it?” is not just a father’s fury directed at a defendant. It sits over two broken families, two children who lost their father, and a web of friends and colleagues who spent 11 years explaining the unexplainable. Courts answer legal questions. That one, no judge can resolve.

As for timing, here’s the realistic path: the pre-sentence investigation usually takes several weeks. The court will hold a sentencing hearing after that — likely later this fall or early winter — and then the appeal clock starts. Meanwhile, prosecutors keep their files open. If the past decade is any guide, they will move when they’re ready, not when the public conversation peaks.

On Wednesday, though, the process belonged to the Markels. In a courtroom finally ready to close one chapter, they got the piece of accountability the system can offer. And they used their moment, not to celebrate, but to stare straight at the woman a jury said helped pay to take their son’s life — and ask her to answer what they have carried for 11 years.